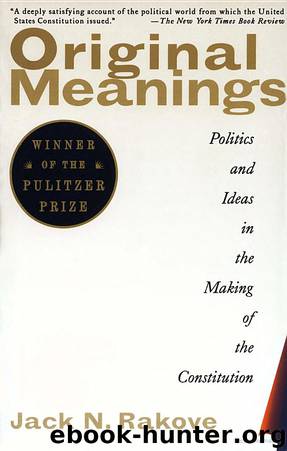

Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution by Jack N. Rakove

Author:Jack N. Rakove [Rakove, Jack N.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780307434517

Publisher: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

Published: 2010-04-21T06:00:00+00:00

Congress was not unique in this respect, for instability in office was a “capital Defect thro[ugh]out our appointments.” To be effective, Jackson noted, government had to be made “the Business of a few—and made their Business both from Motives of Interest and Ambition.” Benjamin Rush echoed this point a year later in his essay decrying the common tendency “to confound the terms of the American Revolution with those of the late American war.” “Government is a science, and can never be perfect in America, until we encourage men to devote not only three years, but their whole lives to it.” No wonder “so many men of abilities object to serving in Congress,” Rush concluded; who would wish “to spend three years in acquiring a profession which their country immediately afterwards forbids them to follow[?]”34

The ostensible target of this complaint was the clause in the Confederation restricting delegates to serving three years out of any six—a clause that numbered Madison among its first victims. That rule was itself the by-product of a cluster of beliefs that were expressed not only in the principle that rotation in office and annual elections were rights belonging to the people or in occasional populist surges among the electorate, but also in the attitudes of officeholders themselves. Throughout the Revolution and afterward, both Congress and the state legislatures suffered from high rates of turnover in membership. Inexperience and inefficiency went hand in hand, and much of the criticism directed against both levels of government could be traced, as Jackson argued, to the lack of a stable corps of capable legislators.35 But this turnover was not primarily the result of the dissatisfaction of voters with the elected. It reflected instead the complaints of incumbents who found the burden of public life more than they wished to bear and who retired from office as soon as they gracefully could. However much homage Americans paid to the ideal of the citizen who virtuously subordinated private interest to public good, few of them learned to prefer the duties of public office to the contentments of private life. The civic life exalted in the classical republican tradition never became the dominant value of political behavior even during the war years, when patriotic appeals ran strongest. In time of peace, its appeal slackened further. The ennui that Madison felt when he was rusticated to Montpelier in 1783 was far less typical than the eagerness with which Cornelius Harnett, another delegate, had looked forward a few years earlier to retiring “under my own vine & my own fig tree (for I have them both) at Poplar Grove,” his North Carolina plantation.36

The notion that politics could become a profession or a business marked a significant departure from the conventional view that it was an avocation best pursued by men whose imminent return to a private station would remind them that they would be governed by the same laws they framed. Experience gained through tenure might support the monitory purposes of representation by enabling “honest but unenlightened” lawmakers to penetrate the “sophistical arguments” of demagogic leaders.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19088)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12190)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8909)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6886)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6279)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5802)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5754)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5507)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5444)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5218)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5153)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5087)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4963)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4925)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4788)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4753)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4718)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4509)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4490)